Key Takeaways:

- Performance vs Learning

- Types Of Practice & The Forgetting Curve

- How Much Time Does It Take To Learn?

We’re talking about practice . . . planning; a coach’s favorite pastime. While there won’t be many drills to steal from this chapter, readers could dive into how different types of practice can reduce the amount of slippage between preparation to gametime.

A loose definition of any practice is to teach or improve skill-acquisition, system comprehension, or future opponent scouting. How often have coaches conducted a shell drill teaching different defensive assignments? Only later, they see someone forget to be in help during the game. Or again during practice, hammering home the concept of sprinting to space in transition during 5v0 offense and somehow the big always seems to be on the outer thirds with the perimeter players. Performing a task immediately after being taught isn’t a strong indicator of retention.

“Performance in training is a false signal. What an athlete demonstrates she can do during a training session does not indicate what she will be able to do in a match. As coaches, we observe training and conclude that the level of proficiency we see then is what we are likely to see in the game. However, during training, athletes have not yet begun to forget; as soon as the session ends, that process begins, and forgetting is a ruthless and tireless enemy.”

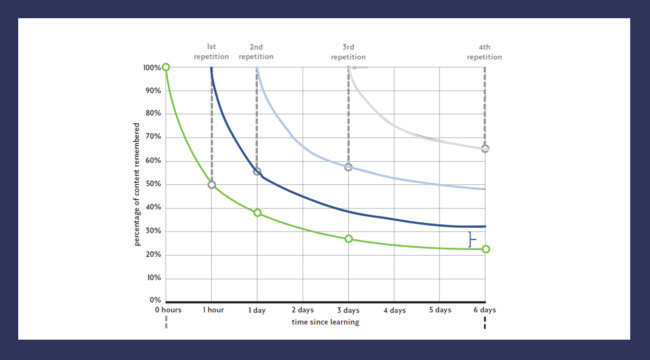

Game slippage appears when players fail to execute in a similar capacity as what was previously performed during practices. Players forget things all the time; matter of fact, according to Lemov’s Forgetting Curve (see diagram below) people start to forget immediately after being taught. So from a coaches perspective the key is to strategically use practice for consistent retrieval.

Types of Practice & Forgetting Curve

Blocked practice. Serial practice. Random practice.

Answering any Happy Gilmore fans out there, well who gives?

Speaking less to the specific drill design as opposed to how they are put together. Different types of practices serve different purposes, and depending on the order or time in between activities players’ retention rates can vary.

- Retrieval Practice – Act of recalling what you have encoded in memory in order to keep from forgetting it and to get better at recalling it.

- Blocked Practice – Practice in a steady unbroken fashion

- Spaced Practice – Delays between rounds of retrieval practice to allow forgetting to begin and thus make the practices more effective.

- Serial Practice – Interleaving multiple activities during training.

- Randomized Practice -Interleaving training with a pattern and timing that is unpredictable and ideally context driven

While I’ll never claim to be the smartest person in the room, from what I gather from the Forgetting Curve; repetition over time leads to more retention. Seems obvious enough, but the graph also could suggest cramming before a championship game could lead to some issues, if trying to install new information. This should force us to consider how are pre-season practice planning is shaped versus regular season going into the post-season. How much installation should be put in during December versus February? If putting in new concepts or actions come February, is it in addition to information previously understood or is it completely brand new?

How Much Time Does It Take To Learn?

“If the key to durable learning is spacing practice out to allow memory to decay in between iterations, this implies that there is almost nothing players can master in a single exposure.”

Based on my interpretation, scouting a day or two in advance of an opponent becomes a combination of performance and execution. Does a team with the capacity to perform better win more? Or does a team with a stronger understanding of principles play within their own system win more?

This is the give and take of a program that has less of a plan for long term development as opposed to winning in the short term. There is not a more prominent display of varying intentions than watching AAU basketball. One team can walk into the gym without having ever practiced and win merely on talented free play. We all know that there is a true separation when talent is balanced from attention to details.

Kelvin Sampson alludes to the all-time coaching aphorism; it’s not what you teach it’s what you emphasize. If anything taught can be forgotten, then anything emphasized can be learned. According to Lemov, a suggested learning interval takes between 4 to 6 weeks.

“Within a four-to six- week unit, you might choose several important topics to focus on: depending on the scale of the topics, perhaps two on the offensive side of the ball, two on the defensive side and one in transition, plus a few technical skills as well.”

Our effectiveness over those 4 to 6 week increments is crucial. It separates teams with hopeful winning performances from those with highly probable outcomes. This is due to intentional player development and system comprehension.

ACTIVITY DESIGN RULES OF THUMB

Author Doug Lemov provides 6 general rules when designing a plan to optimize learning or retrieval:

- Have a targeted goal

- Practice in rounds

- Isolate then integrate

- Mix in mix-ins

- Manage extrinsic load

- Adapt to level of expertise

Rules 3-5 generally speak to progressively stacking the learning to increase general knowledge, yet being aware of how much new information is being processed.

Ultimately, practices should be a constant training ground of familiarizing concepts of play while progressing turning up the dial of difficulty. Quick fixes are harder to apply if installing new information – which is why gameday scouts could be more rehearsal of previously practiced drills as opposed to memorization of opponent playbooks. Keep in mind that what has been taught can always be forgot, so simple reminders support consistent retrieval.