Key Takeaways:

- Economy of Language & Emotions

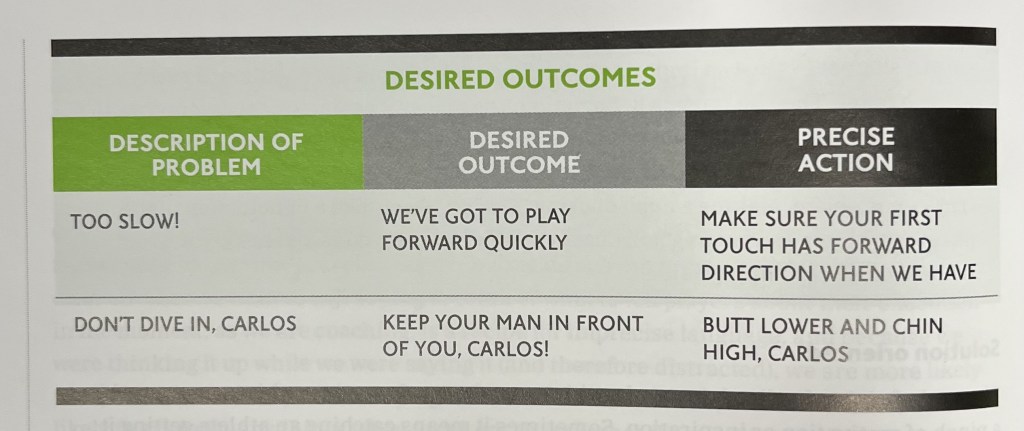

- Correct Instead of Critique (Desired Outcomes)

- Exemplar Planning (To Win)

“Good feedback essentially helps athletes believe in the coaching process.”

Arguably one of the strongest separations between quality of coaching comes from the value offered from our feedback. Maybe not so much the proficiency of instruction – competency certainly plays a part – but, rather establishing a level of confidence and comprehension from the accumulation of coach-to-player interactions. The coaching process has the ability to empower player development or fracture their confidence based on our reactions.

Any casual fan or former player can put together a lineup and call out a couple of designed plays. But, what happens when a team fails to execute, or a particular player has a sequence of possessions with incorrect reads? This conversation is not for social media platforms. In the realm of reality; the difference between a casual coach versus calculated teacher understands the butterfly effect from our ability to communicate. In this chapter, author Doug Lemov breaks down a few of his core principles to feedback – starting with trust.

“Trust is an outcome of feedback as much as a prerequisite.”

Feedback 101 – Economy of Language & Emotions

In my first post – Ability To Decide – I mentioned how this book can come off as a textbook. Feedback was appropriately broken down into 101 to 301 classroom style segments.

It’s not what you say, but how and how much it takes to say it. The economy of language is how we effectively deliver feedback in the most efficient way possible. Something I fight to improve upon year over year. This season, I’ve picked up a communication concept where I’m currently coaching where the team is taught the distinction between critical and casual conversation.

For the most part, practices offer an opportunity for coaches to engage in more 2-way conversations where an instruction can be followed by a check for understanding or clarification. During games, the message tends to be unilaterally coded into abbreviated reminders that hopefully resonate most with the players and team. This is referenced as a form of fast feedback in the book.

Casual or critical, the substance of the message can be diluted in a few different ways. One example is doing too much. Instead of being concise, our instruction becomes convoluted by saying the same thing in 3 different ways. Another way to muddy a message is by simply identifying the problem without a solution. As a point guard, the thing I hated most – which must have happened to often – is hearing, “Stop turning the ball over!” There is an obvious instruction, but isn’t always targeting why the issue keeps repeating itself. The last one mentioned is a byproduct of dealing with repetitive mistakes: our emotional response. Lemov acknowledges intensity is part of the game, but demonstrating emotional constancy is a way for players to absorb feedback without distractions.

Feedback 202 – Correct Instead of Critique

If the objective is to correct a behavior, then the feedback should be focused on precise action. The example above is from the book illustrating the differences between simply shouting out the problem to requesting a result versus being specifically prompting a better approach.

Lemov shares a few ways coaches accomplish this:

- Challenging With A Question

- Affirmations or Assuming The Best

- Word Association From Film or Professional

- Prompting Self-Assessment

Some of it gets kind of flowery, but you get the point.

Coaches play to their disposition to authentically help players improve an understanding for what works and what is counterproductive. But, then what if players are just not coachable?

“So when we talk about coachability, our assessment should have more to do with how people use feedback than how they take it. If we want to get better at improving people, we have to “win the after.” We have to cause productive action.”

“Win the after,” is a really good line.

And this corresponds a lot to the E(vent) +R(espond) =O(utcome) mantra.

If application of coaching is rooted in trust, then a players coachability comes from a combination of timeliness and alignment. Lemov touches on shortening the loop, which refers to correcting a behavior as close to when it occurred as possible. Keep in mind, this comes with balancing the frequency of stoppages with what’s most important. Becomes a fine line between what once was at least heard now becomes selective listening.

There is a point made about the sins of diligence or enthusiasm. No player wants to make a mistake. Some are more prone to them than others, whether out of fear for making a mistake therefore acting without any natural anticipation while others are too aggressive hoping to make the big play.

“A good coach can teach more in 90 minutes than players can absorb. We have to pick and choose what we talk about. We have to know what it’s most important to coach and focus on coaching those things well.”

Feedback 303 – Exemplar Planning To Win

Part of mitigating the sensation to constantly intervene during practices is in our preparation. Exemplar planning is envisioning a perfect version of practice and anticipating the errors or margin between what would be considered good versus great.

Here’s a 4-step process that the author puts together as a coach’s activity for professional development:

- Write out your training objective for the practice or workout. Be specific.

- Write out an exemplar practice plan. In detail, what should happen?

- Anticipate at least 2 errors. What will the players get wrong most?

- Plan the responses.