Key Takeaways:

- Game Intent

- Purist vs Modernist

- Influence of Coaching Philosophy

And when Detroit and San Antonio ended up in the 2005 NBA finals, sports columnists noted that this would be a series for basketball purists.

PAGE 31

The matchup between legendary coaches Gregg Popovich and Larry Brown was only 15 years ago. But, with guys on the floor nicknamed ‘The Big Fundamental’, ‘Rip’ Hamilton, and ‘Big Shot Billups’ you’d think it would’ve been only viewable on a black and white television screen. For reference, it was a 7-game series that played out as advertised. Defensive performances by both teams keeping an opponent below 80 points in 5 of the 7 games. Offensive fundamentals exhibited inside and out with the Detroit Pistons setting an NBA Finals record of only 4 turnovers in Game 4 to tie the series 2 games apiece. Ultimately, ‘The Big Fundamental’ and the San Antonio Spurs would become the eventual 2005 NBA Champions.

From a media and national publication standpoint the 2005 NBA Finals epitomized how the game was intended to be played: fundamentally sound offense with a lot off-ball action and unforgiving defenses. On the flip side, the San Antonio Spurs tend to be on the wrong side of the viewer ratings when in the Finals insinuating the average fan is less interested in fundamentals than run-and-gun. Basketball And Philosophy discusses which brand of basketball is better – the good ‘ol days (purist) or the new age (modernist).

“Back in my day…”

Fans of each generation have a subjective view of the best brand of basketball despite evidence of overlap between each era. During my day we played team defense. During my day we moved without the basketball. During my day, then just fill in the blank from what you have heard because everyone has a barbershop type story to tell.

Debates divide based on the perspective of how the game was intended to be played, not on what style of play leads to more wins.

Arguments between purists and modernists are primarily about different visions of what basketball should be, not about which techniques work better.

PAGE 33

The chapter moves the discussion forward on how the game was started. James Naismith originally developed the sport as an activity for kids during the winter season. The rules put in place emphasized accuracy over speed without shot-clocks and the basket mounted on a flat surface with a horizontal area to score points. Or fouls put in place to encourage agility over brute force. If you want an easy way to identify purist and modernist, put out on social media that “__(State)__” high-school basketball needs a shot-clock.

Meanwhile, the author breaks down the essence of “gamewrighting.”

Good games, in short, provide good tests.

But regardless of the uses to which games are put, the fundamental principle of gamewrighting remains the same. It is to create a good test.

PAGE 36

Coaches use sport situations as analogies to life lessons all the time. The essence of any game is to create complexities that challenge our individual development, whether it is sport-specific or cognitive training. And our perspectives of the best brand of basketball often mirror pushing our players to maximize individual abilities for a collective purpose to compete within the confines of the rules of any game. From that, we hope values are instilled that become transferable to future success in life.

Purists vs Modernists

The interesting concept to think about between the purist-modernist debate is our biases as a fan and how it can influence our coaching philosophies. Strictly speaking on the court, if you grew up in an era that embraced ’40 Minutes of Hell’ from the Nolan Richardson era it is likely that pressing for the entire game is a style of play that appeals to you. Is that an old-fashioned way of playing?

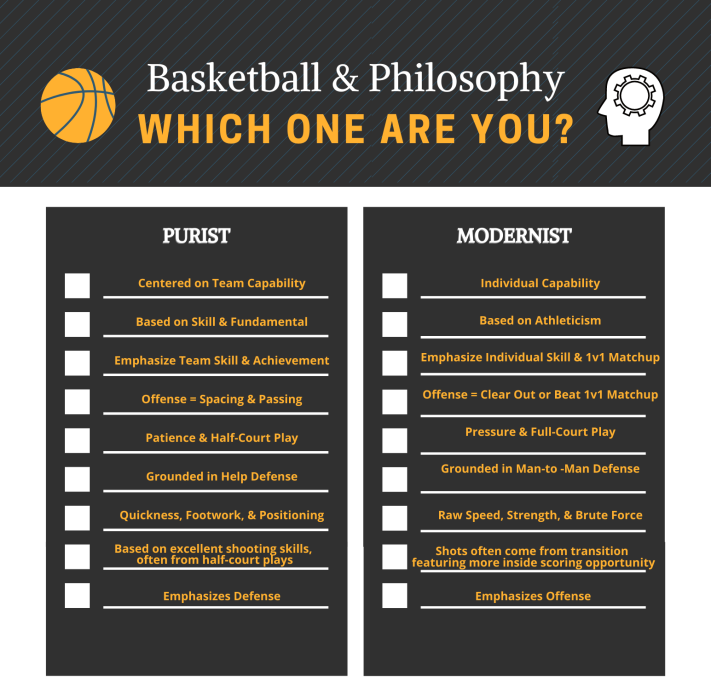

According to the chart above (used in the book), that style of play would lean more towards a modernist philosophy with a focus on athleticism, raw speed, and preferring to stay in transition throughout the game.

Consider the early interest in the game, as a fan or as a player. What drew you to the sport?

- The pace

- Making shots

- Camaraderie

- Outsmarting opponents

As an early rec-ball player, it was all about speed and the open floor. I was small and quick, so I’d look to get steals and layups however they came. Which opened my eyes to off-ball defense – maybe, if I leave my man when that ballhandler isn’t looking I can get a steal. The cat-and-mouse aspect stimulated my desire to become a point-guard: more control, more directing, and more manipulation of the opponent. The purist form of basketball to me was to outsmart the opponent and score the most points.

Coaching Philosophy

I think any coach would agree with that concept; it is all about how we decide to move the chess pieces to accomplish the same objective. The fascinating part of our game is the ever-evolving dynamics or skillset athletes continue to demonstrate. From not jumping to shoot when the game originated to Damian Lillard hitting game-winners a step off the logo at mid-court.

Our responsibility is to be a continual-learner of the game. So, while I am not advocating a eurostep before pro-hop off two-feet finishes; I do understand there can be utility in the move at the right time of development. As it pertains to the style of play, my observation is the best programs that often win the most have a system with continuity of concepts. Therefore, my favorite brand of basketball has embraced a combination of Davidson in the breaks, Villanova as a base offense, and a hybrid of Virginia on the halfcourt defensively tossed in with West Virginia full-court pressure.

The purist and modernist debate breaks off into the rules of the game and situational decorum. All of which coincides with our adaptability or commitment to standards. This conversation largely stays on the floor. In the end, my guess is everyone is a purist, just maybe under the cloak of a modern style of play.

One thought on “Basketball And Philosophy: Purist Game”